- In a message to Grand Duke Nicholas today, Joffre outlines the two major objectives of the French offensives that begin tomorrow:

The objective of these actions is twofold: (1) hold the enemy in front of us in order to facilitate the general action of allied forces; (2) make a breach in one or more points on the front, then exploit this success with reserve troops by taking the enemy in the rear and forcing him to retreat.

The first point is designed to alleviate the Russian commander's concerns regarding French inaction on the Western Front allowing the Germans to redeploy further units eastwards, while the second illustrates that Joffre saw the battle as a relatively-straightforward attack designed to achieve a breakthrough, from which would ensue a return to mobile warfare. Joffre, though, did recognize that the present circumstances on the Western Front required different tools to achieve the breakthrough, weapons akin to thus utilized in siege warfare. As he noted to the Grand Duke, should the attacks fail it would be because they were launched 'with still insufficient means.'

- In the early morning hours Hipper's battlecruisers and their escorts the British east coast. The plan is to divide into two forces, the first to bombard Scarborough and Whitby, the second to strike Hartlepool just to the north. The weather, however, is deteriorating, with rising seas and high winds. The weather becomes sufficiently serious to pose a risk to the light cruisers and destroyers, so at 653am Hipper orders them to turn back and sail eastward towards the Dogger Bank where Ingenohl and the High Seas Fleet are to be waiting.

|

| The German battlecruisers Seydlitz, Moltke, and Derfflinger during the Scarborough Raid, as taken from Von der Tann. |

An hour earlier, however, the situation around the Dogger Bank had changed decisively. As the High Seas Fleet was approaching Dogger Bank, the British battlecruisers under Beatty and the dreadnoughts of Warrender's 2nd Battle Squadron were to the northwest of Dogger Bank, sailing to their patrol point to the southeast. By a supreme coincidence the course of the two fleets brought them into close proximity to each other, neither knowing that the other was nearby. At 515am the seven British destroyers escorting Beatty's and Warrender's force are ten miles east of the dreadnoughts when they stumble upon several German light cruisers and destroyers, the latter being the advance screen of the High Seas Fleet. For the next forty minutes there is confused, short-range fighting between the two forces, with the British suffering the most - three of their destroyers are severely damaged.

As the fighting continued the captains involved signalled their main fleets that they were engaging the enemy. At 523am Ingenohl, aboard his flagship

Friedrich der Grosse, is informed that German destroyers are fighting their British counterparts to the east, and the flashes of gunfire are visible on the horizon. He does not know the composition of the British force opposing him, which allows his worst fears to run wild. What if these British destroyers are the advance screen of the entire Grand Fleet? This would mean that the High Seas Fleet was almost certainly sailing towards its destruction. He was ever-mindful of the Kaiser's edict: no general naval battle is to be risked. In the dark of night, Ingenohl comes to believe that this is exactly what is about to happen. At 530am he signals all of his squadrons to reverse course and turn southeast for home.

It was a monumental decision, even leaving aside the fact that Ingenohl's retreat left Hipper's battlecruisers abandoned without even so much as a signal indicating the fleet was returning to Wilhelmshaven. It meant that Ingenohl was turning away from the greatest opportunity the German navy was to have in the entire war to engage an isolated portion of the Grand Fleet. If Ingenohl had not lost his nerve, a battle between his fourteen dreadnoughts and the six dreadnoughts and four battlecruisers of Beatty's and Warrender's force would have likely occurred at dawn. The British would certainly have dealt out serious damage, but the High Seas Fleet would have had the advantage and the most likely outcome of such a battle would have been the loss of significantly more British warships than German. Such a victory in turn would have given the Germans parity in the North Sea - at no point before or after December 1914 would the two fleets be closer in size, and the British margin of superiority would have been erased by the losses such a battle would likely have resulted in. Thus by turning away, Ingenohl threw away the best chance the Germans would ever have to change the course of the war at sea. While Ingenohl bears responsibility for the order, it bears recalling that it was given in line with the instructions of the Kaiser. Ultimately, it was the Kaiser's own unwillingness to risk defeat that ensured he never won the great naval victory he yearned for.

While Ingenohl was making his fateful decision, confusion reigned in the British force. Admiral Warrender, who as Beatty's senior was in overall command of the operation, had been informed that several of his destroyers were engaging the enemy, but they had failed to signal positions, courses, or speeds. Concluding that any small German warships could be swept up after Hipper's battlecruisers were dealt with, Warrender decides that instead of turning east towards the fighting, his dreadnoughts will continue southeast towards the morning rendezvous. By 730am Warrender's dreadnoughts, Beatty's battlecruisers, and Rear-Admiral Goodenough's light cruisers had arrived at their patrol point just off the Dogger Bank. Confused signals continued to come in from British destroyers to the east, with some being missed. Just as Beatty decides to charge eastwards to engage the Germans, word comes that the British coast is being shelled. Beatty abandons the chase, and the British warships at sea turn westward to intercept Hipper.

The German bombardment had begun at the town of Scarborough at 8am by the southern part of Hipper's force, consisting of the battlecruisers

Derfflinger and

Von der Tann, plus the light cruiser

Kolberg. Out of the morning fog bright flashes were followed by shells crashing into buildings. For a half-hour the three warships fire, and when they depart at 830am seventeen people were dead and ninety-nine wounded - all civilians. These three warships then sailed twenty-one miles up the coast to the fishing village of Whitby, which they bombarded for ten minutes, killed two and wounding two more. The northern part of Hipper's force, comprised of the battlecruisers

Seydlitz,

Moltke, and

Blücher (the latter variously classified as a battlecruiser or armoured cruiser - regardless, it was the weakest of the three), was approaching the shipbuilding and manufacturing town of Hartlepool when at 750am they encountered four elderly British destroyers patrolling offshore. Though one manages to close sufficiently to fire a torpedo, it misses and otherwise the destroyers retreat under a hail of German shellfire. When a light cruiser in Hartlepool attempts to put to see, it is struck by two shells and ran aground. This was the only naval resistance the three German warships would encounter at Hartlepool, and while several shore batteries did keep up a constant fire, their 6-inch shells were unable to pierce the armour protection of the enemy battlecruisers. The German bombardment of Hartlepool lasts from 810am to 852am, during which the three battlecruisers fire 1150 shells at the town. Shells rained down on the shipyard and the steelworks, but also damaged more than three hundred homes. When the Germans depart, eighty-six civilians were dead and 424 wounded. Damage to the six warships was minimal, and only eight sailors were killed and twelve wounded.

At 930am the two parts of Hipper's force reunite and turn for home, fifty miles behind the light cruisers and destroyers he had sent home earlier in the morning. He signals Ingenohl his course and speed, and asks for the location of the High Seas Fleet. Ingenohl's reply is that it is returning to port. Hipper's response is a rather colourful curse - Ingenohl's hasty retreat has abandoned the battlecruisers to their fate.

On the British side, Beatty and Warrender believe that they will soon be able to find and annihilate Hipper's force - there is a gap fifteen to twenty miles wide between two minefields on the Yorkshire coast through which Hipper must sail, and both British forces are heading for this point. At this point the British are stricken with almost comically bad luck. First, the weather in the North Sea deteriorates rapidly, drastically reducing visual range. Second, at 1125am the British light cruiser

Southampton, part of Goodenough's cruiser squadron, sights several enemy light cruisers and destroyers - these were the warships Hipper had sent home early due to the rough weather. Goodenough signals Beatty that he is engaging the enemy, and orders the other three light cruisers of his own force to assemble on

Southampton. Goodenough's cruisers had been tasked with scouting ahead of Beatty's battlecruisers, a vital task in the poor weather, and Beatty, not knowing

Southampton has met multiple enemy light cruisers, is dismayed to see all of his light cruisers turn away to follow

Southampton. He tells his Flag Lieutenant to signal 'that light cruiser' to resume its station ahead of the battlecruisers. The Flag Lieutenant, uncertain which light cruiser Beatty is referring to, tells the signalman, using his searchlight, simply to order the 'light cruiser' to resume its station.

Nottingham, the light cruiser receiving the signal, believes the signal, given that it names no specific light cruiser is for the entire squadron, and passes it to Goodenough. The latter, believing he has received a clear and direct order from a superior officer, breaks off the fight with the German warships and orders all of his light cruisers to return to the battlecruisers. The German light cruisers and destroyers disappear in the distance, and when Beatty sees all of Goodenough's light cruisers returns he is apoplectic, believing Goodenough has allowed Hipper's screening force to escape. In reality, the problem was down to a misunderstood signal, not the last time such a problem would bedevil Beatty.

At 1215pm the same German warships that Goodenough had allowed to escape is sighted by some of the dreadnoughts of Warrender's squadron. However, Warrender himself cannot see them, and so never issues an order to fire. The dreadnoughts that do see the enemy believes that Warrender must have some reason for not yet firing, so they never open fire on their own initiative. The German light cruisers and destroyers then disappear again into the rain, a second miraculous escape.

Beatty aboard his flagship

Lion believes that the German warships sighted, then lost, by Goodenough and Warrender are the immediate screening force for Hipper, and that the German battlecruisers must be just behind them. This leads Beatty to conclude that when the light cruisers and destroyers slip past Warrender, that Hipper's battlecruisers must also be about to escape. To prevent this, at 1230pm Beatty orders his squadron to turn to the east, believing that only his ships had the speed to cut off the Germans from their home base. The reality, of course, is that Hipper's battlecruisers were fifty miles behind the light warships. If Beatty had kept to his original course, he would have almost certainly ran right into Hipper. By turning away, he opened a gap between the minefields that Hipper promptly sailed through. By the time Beatty realized that the German battlecruisers were not in fact in front him, Hipper had slipped away to the north. Several hours of frantic searching by Beatty and Warrender find nothing, and by late afternoon they conclude that the Germans have made their escape.

The bombardment of Scarborough, Whitby, and Hartlepool caused outrage in Britain, compounded by the fact that the raiders had escaped. In the Royal Navy there was immense disappointment that what had seemed like a golden opportunity to destroy the German battlecruisers had gone to waste. There was infighting as the different admirals assigned blame to others, Beatty being particularly hard on Goodenough. In practice luck and the weather had been against the British this day. The muddled chase also showed the limitations of Room 40; though it had correctly detected the battlecruiser raid, they did not realize the entire German fleet was at sea, and the delay inherent in decyphering of signals also played a role - a signal by Hipper giving his position at 1245pm, when he could still have been intercepted, was intercepted but not decyphered and retransmitted to Beatty and Warrender until 250pm, by which time Hipper was long gone.

In Germany the raid was celebrated - naval honour was restored, and the hated British enemy was not quite so safe as it had thought it was behind its Channel frontier. Within the German navy, however, the realization of the opportunity Ingenohl had let pass was a bitter pill to swallow. Much criticism was heaped on the High Seas Fleet commander, including from the Kaiser himself, who informed Ingenohl that he had been too cautious, a case of misplaced blame.

Perhaps the most important impact of the raid, however, was on the morale of the British public. To most in Britain, the deliberate bombardment of largely-undefended coastal towns was an atrocity. The overall number of civilian dead - 105 - seems almost pitifully small from the vantage point of the 21st-century, where the record of the past hundred years has left us almost numb to the notion of civilian casualties in war. From the perspective of Britain in 1914, however, the notion of deliberately targeting civilians was seen as something that no civilized nation would ever do - it was in line with the thinking, then much prevalent, that no civilized nation would torpedo merchant ships without warning. The Scarborough Raid, as it becomes known, is quickly held up as yet another example of German barbarism and perfidy, taking its place alongside the Rape of Belgium to show why the war must be fought and why the Germans must be defeated, no matter the cost. The episode becomes a staple of recruiting posters, which emphasize the murder of women and children at the hands of heartless German sailors, imploring the men to avenge the dead and protect those still living - another example of drawing on gender roles to support the war effort. The memory of the Scarborough Raid live in the minds of the British public long after the physical damage had been repaired.

|

Two classic British recruiting posters drawing on memories of the Scarborough

Raid - whole books could be written on the gender themes implicit in them. |

- In Poland the Russian 1st Army, northernmost of the Russian armies in the great bend of the Vistula River, had responded to Grand Duke Nicholas' order to retreat by fleeing as fast as possible east over the Bzura River. To its south, the Russian 2nd and 5th Armies have only begun their retreat, meaning their northern flank has been uncovered by the hastiness of 1st Army. General Mackensen of the German 9th Army believes an opportunity exists to envelop the Russian 2nd and 5th Armies, and while ordering his northern wing to attempt to outflank the enemy south of Sochaczew, he also requests that the Austro-Hungarian 2nd Army to send a detachment to the northeast towards Lubochnia to form the other half of the pincer movement.

- South of the Vistula River, the Austro-Hungarian pursuit of the retreating Russian armies continues to be stymied by strong rear-guard actions that limit their advance and result in hard fighting, suggesting that the Russians do not intend to withdraw a great distance. Despite this, Conrad continues to believe that the Battle of Limanowa-Lapanow is a crushing victory, and his major concern today is how to bring the Russians to battle before they can retreat across the San River.

- Overnight the schooner

Ayesha endures a violent storm that tears away all of the forward sails, leaving it at the mercy of the ocean. In the morning, however, the storm vanishes, and

Ayesha is left adrift when the wind proves too light to fill the remaining sails. Fortunately

Choising appears, and takes

Ayesha in tow to the sheltered bay of a nearby island, where

Emden's landing party transfers to the merchant ship. They make

Choising their new home, bringing with them all of their provisions and weapons. The decision is made to sink

Ayesha, to prevent it either falling back into British hands or from revealing their most recent position. After cutting two holes in the hull,

Ayesha is cut adrift as

Choising's engine is started at 4pm. For some time

Ayesha continues on its own to follow

Choising, and the Germans decide to halt to watch its final minutes. At 458pm the

Ayesha plunges out of sight, and the Germans give three cheers to honour their former ship.

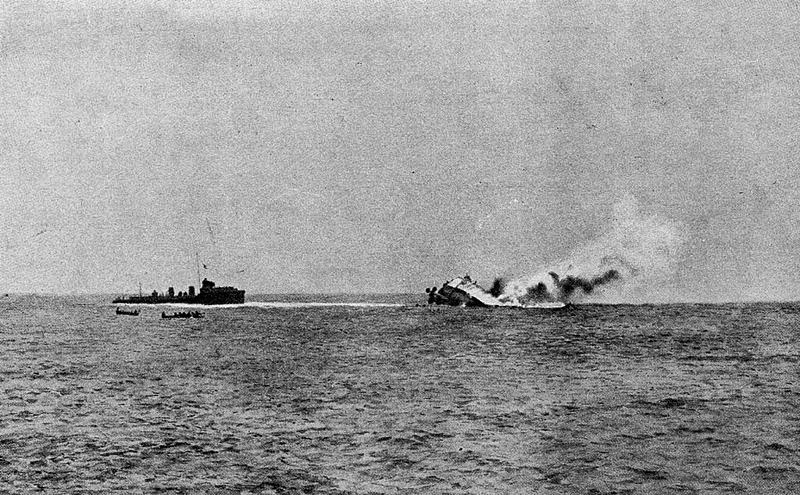

|

| The schooner Ayesha. |

Aboard his new ship First Officer Mücke must decide where to sail next. His original plan on leaving Padang was to try to reach the German colony of Tsingtao in China, but on boarding

Choising they had learned of its fall over a month ago. Sailing to German East Africa was quickly dismissed, as the arrival of fifty under-equipped and poorly-armed sailors could not possibly make a difference to the fighting there. Joining with

Königsberg was similarly ruled out. It appeared the only option was to sail around Africa until a report in one of the newspapers aboard

Choising mentioned a skirmish between British and Ottoman forces in Arabia. Mücke thus decides that the best option is to sail to Arabia and return to Europe overland through the Ottoman Empire. The slow speed of

Choising - between four and seven knots per hour - means the voyage to Arabia will take several weeks. In an effort to avoid suspicion, the crew disguises

Choising as the Italian merchant ship

Shenir, complete with an Italian flag made of a green window curtain, white bunting, a strip of red, and a painted coat of arms.