- Even as the German government attempts to defend its conduct of the war, the latest outrage - the sinking of the passenger liner Lusitania - is provoking a violent reaction in Britain, especially in Liverpool and other west coast ports in which many of the dead resided. For these civilians, the torpedoing of Lusitania is seen as culmination of a German campaign of deliberate barbarism that has included the Rape of Belgium, the bombardment of Scarborough and other towns, Zeppelin bombing raids, and the use of gas at Ypres. For many the news of Lusitania's loss is the final straw, and over the past few days anti-German riots have broken out in several British cities, including most prominently Liverpool, the destination of the doomed liner. Large crowds rampage through commercial districts, attacking any shop identified as being owned by Germans and looting its contents. Local police struggle to maintain order, with hundreds arrested. Today is the worst day of violence in Liverpool, and hardly a single commercial enterprise owned by a German remains unscathed at the end of the day. While the violence builds on existing anti-German sentiments and indeed xenophobia, they also arise from the general sense among the British public that the German methods of waging war are a fundamental threat to Western civilization, and that the war is not only worth fighting but must be fought until absolute victory can be secured and 'Prussian militarism', as it is often referred to, is crushed forever. Whether right or not, such views are genuinely held by much of the British public, and go some way to explaining the overwhelming support for the continuation of the war in the months and years ahead.

|

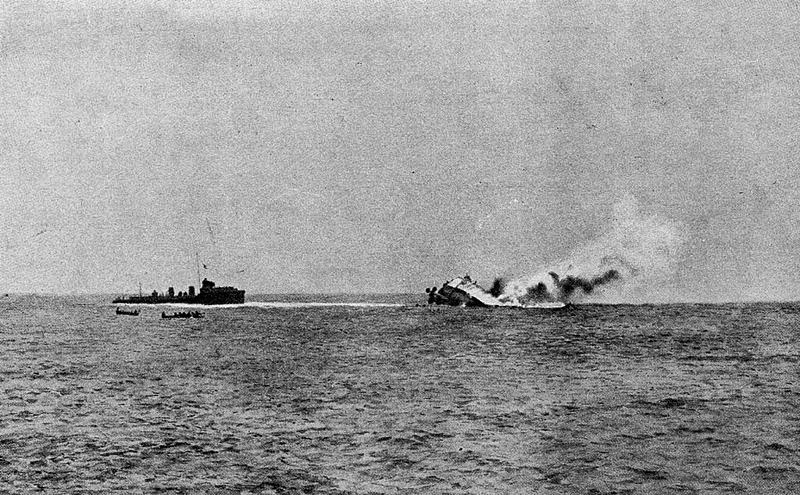

| The aftermath of the Lusitania riots. |

- A more measured reaction to the sinking of Lusitania is seen today in the United States when President Woodrow Wilson delivers a speech before fifteen thousand in Philadelphia. After several days of deliberation, he has come to the conclusion that an immediate declaration of war is not the proper course of action. More crucially, imbued with a moral sense of American righteousness, he proclaims to the assembled crowd that:

. . . the example of America must be a special example . . . the example, not merely of peace because it will not fight, but of peace because peace is the healing and elevating influence of the world and strife is not. There is such a thing as a man being too proud to fight. There is such a thing as a nation being so right that it does not need to convince others by force that is is right.Wilson's proclamation is greeted by prolonged cheering. In Britain, perhaps not surprisingly, the president's words are not so welcome - Wilson's high-minded rhetoric appears completely divorced from the perceived reality of a struggle for civilization, and there is little inclination to take lessons in morality from someone whose country is resolutely on the sidelines.

- In Germany, reaction to the sinking of Lusitania has been mixed. Much of the public, convinced that the liner was carrying munitions, celebrates its destruction, as does the naval leadership. For the Chancellor and the Kaiser, the sinking is seen as a disaster. Wilhelm II directly orders the naval chief of staff that

. . . for the immediate future, no neutral vessel shall be sunk. This is necessary on political ground for which the chancellor is responsible. It is better than an enemy ship be allowed to pass than that a neutral shall be destroyed.Learning of the Kaiser's order, Bethmann-Hollweg informally conveys to Washington that German submarines have been instructed to avoid neutral vessels. Unfortunately for the pair, the naval chief of staff is committed to unrestricted submarine warfare, and in an act of deliberate insubordination does not convey the Kaiser's order to the fleet. For now the ostensible leaders of Germany are kept in the dark.

- In Artois today the French 10th Army attacks all along the German line, attempting to repeat the fleeting success of yesterday. Overall the French attacks fail: an attempt to move further east on the Lorette spur was held, and repeated attacks by 70th Division at Carency were also repulsed. However, a German counterattack by elements of 58th and 11th Divisions also fails, and the French XXXIII Corps is able to maintain control of the ground seized yesterday. This salient also leaves German positions at Carency and Ablain just to the north almost isolated, and the commander of the German 28th Division, responsible for this section of line, is concerned that the villages may have to be abandoned.

Further north, in light of the complete failure of the attacks of yesterday, Sir John French calls off the British offensive towards Aubers Ridge early this morning. General Haig, whose 1st Army had been responsible for the operation, is dismayed at the failure. Writing in his diary, he concludes that the defeat 'showed that we are confronted by a carefully prepared position, which is held by a most determined enemy, with numerous machine guns.' To overcome such defences, Haig believes that an 'accurate and so fairly long' preliminary bombardment will be necessary in future to ensure enemy strong points are destroyed before the infantry advance. However understandable Haig's conclusions may be, he is learning the wrong lessons.

- Overnight the Russian counterattack in Galicia is launched, with 44th Division advancing towards Jacmierz into the gap between 11th Bavarian and 119th Divisions and 33rd Division to the south advancing towards Besko. Though the Russians are able to initially gain some ground, the German commanders are more than equal to the task. To the north, 11th Bavarian Division pushes back the southern flank of XXIV Russian Corps to the north, which creates space for the German 20th Division to come up from its reserve position and launch a attack co-ordinated with 119th Division on the Russian 44th Division, throwing the latter back. To the south, the Austro-Hungarian X Corps secures the high ground near Odrzechowa, threatening the flank of the Russian 33rd Division. By nightfall the Russians have been repulsed and are retreating eastward towards Sanok.

The counterattack by the Russian XXI Corps had been the last throw of the dice for 3rd Army, and its defeat means any hope of holding the Germans west of the San River has evaporated. General Ivanov's chief of staff sends a despondent message to Stavka this evening, stating that the army is shattered and the situation is hopeless, and the only option is a pell-mell retreat eastwards: Przemysl will have to be surrendered, the Germans will soon invade the Ukraine, and Kiev should be fortified. The chief of staff is promptly fired, but Stavka finally acknowledges reality and finally acquiesces today to General Dimitriev's repeated requests to retreat behind the San, 3rd Army is a mere shell of its former self. Of the 200 000 men it had on May 2nd, only 40 000 remain to retreat eastwards today, and this despite 3rd Army having received 50 000 replacements in the meantime. Further, the Germans have taken 140 000 prisoners, reflecting the shattered morale of the Russian infantry. Some of its formations have simply ceased to exist: IX Corps has suffered 80% casualties, while III Caucasus Corps, which was sent into the battle on May 4th to restore the situation, has instead lost 75% of its strength in the six days since.

The strategic implications of the crushing defeat suffered by 3rd Army also continue to spread. In order to maintain some semblance of coherent line on the Eastern Front, Stavka issues orders for the southern flank of 4th Army to pull back east almost to the confluence of the San and Vistula Rivers, while 8th Army in the Carpathians will have to retreat to the northeast and reorientate to face to the west instead of the south.

|

| The German offensive at Gorlice-Tarnow, May 10th to 12th, 1915. |

- Though the Treaty of London had been signed on April 26th, details remained to be finalized regarding the nature of Italian co-operation with the Entente, and at sea Italy is in particular eager to secure substantial naval support in the Adriatic. Today in Paris a naval convention is signed between Britain, France, and Italy which calls for the creation of an allied fleet in the Adriatic under Italian command, to which the French would contribute twelve destroyers, a seaplane carrier, and a number of torpedo-boats and submarines, while the British pledged to dispatch four pre-dreadnoughts and four light cruisers. The British reinforcements in particular, however, are to be drawn from the fleet off the Dardanelles, and will not be sent to the Adriatic until they have been replaced by similar warships from France. This detail will be the source of friction between the allies once Italy formally enters the war.

- For Italian Prime Minister Salandra and Foreign Minister Sonnino, the driving force behind Italian intervention on the side of the Entente, the struggle now is to carry the rest of the Italian government with them into the war. This is no easy task, as many politicians do not share their passionate desire for intervention. Instead, a vague desire for neutrality is the most common sentiment, a position to which some within the Cabinet itself adhere to. Moreover, King Victor Emmanuel is unreliable; just yesterday he proclaimed to Salandra his uncertainty as to the right course of action for Italy and the possiblity of abdicating in favour of his uncle the Duke of Aosta. There is also the necessity of securing a majority in parliament for war, which is far from assured. Finally and perhaps of most concern to the Prime Minister and Foreign Minister, there is an alternative political leader known to oppose intervention: Giovanni Giolitti, who has served as prime minister on no fewer than four occasions from 1892 to 1914. The possibility exists that if Salandra and Sonnino cannot carry either the cabinet or parliament in support of intervention, Giolitti may form a government pledged, at minimum, to strict neutrality, if not a pro-German attitude. Indeed, when German Ambassador Bülow browbeats the Austro-Hungarian ambassador today to agree to further concessions, he communicates the offer not to the goverment but to Giolitti; the Germans see Giolitti as the last chance to keep Italy out of the war.

For all of the difficulties that Salandra and Sonnino face, the forces opposed to intervention are not without their own problems. Giolitti is 73 years old, and both his grip on and influence in Italian politics is not what it once was. He also has little desire to form a government led by himself, fearing he would be branded as a lackey of Austria, and crucially communicates this belief to Victor Emmanuel in an interview this afternoon, which does much to calm the nerves of the king. Salandra and Giolitti also meet this afternoon, and the former sufficiently dissembles to leave the latter with the impression that he is not wholeheartedly committed to war. Still, it is possible that Giolitti may still instruct his supporters in parliament to vote against the war when it reconvenes on May 20th. The next ten days will thus determine not only whether Italy enters the war, but indeed the future course of Italian politics overall.

- Today Admiral de Robeck cables the Admiralty a proposal for a renewed naval attack on the Dardanelles. The suggestion originated in a meeting with Commodore Keyes, who remains a strong advocate of naval action, and is convinced that futher naval pressure can yet secure victory. Robeck is more doubtful, and his message reflects his continued pessimism. Even if a naval attack succeeds, 'the temper of the Turkish army in the peninsula indicates that the forcing of the Dardanelles and subsequent appearance of the fleet off Constantinople would not of itself prove decisive. These are hardly fighting words, but Keyes hopes that even a tepid proposal will inspire Churchill to order another attempt.

- Near the mouth of the Bosporus the Russian Black Sea Fleet makes another appearance to bombard the forts, and this time the recently-repaired ex-German battlecruiser Goeben makes a brief appearance. The Germans are dismayed to discover that the 12-inch guns of the outdated Russian pre-dreadnoughts can still fire farther than the 11-inch guns of Goeben. After the battlecruiser takes two glancing blows it uses its superior speed to break off the battle and return to the Sea of Marmara.

%2C%2Blying%2Bdead%2Bby%2Btheir%2B2.75%2Binch%2Bmountain%2Bgun%2Bduring%2Bthe%2BBattle%2Bof%2BNeuve%2BChapelle..jpg)

%2Bin%2Bthe%2Bfront%2Btrench%2Bat%2Bthe%2BAisne%2C%2BSeptember%2B22nd%2C%2B1914.jpg)